sections below (click to jump):

This page primarily discusses adapters that allow you to charge your non-Tesla car at a Tesla charging station, but the reverse case (Tesla car at non-Tesla charging station) is also covered in the background farther down.

There are basically two kinds of charging: slow / AC (called Level 1 and Level 2) and fast / DC (called DC Fast Charging or DCFC). For each case, to use the “other” plug you’ll need an adapter, and there is no single adapter that covers both Level 1/2 and DCFC usage (at least, not yet). In other words, to do both, you’ll need two adapters. However, you might only need one of the adapter types — perhaps you only need to have a Level 2 adapter for overnight charging at hotels, or you only need a DCFC adapter for quick charging during long highway legs in very remote places.

If you look at online retailers you will find countless adapters that do this, but there are two hugely important things to consider that they may not tell you about:

The safety standard for EV charging adapters is UL 2252. You have to pay big bucks to see the actual standards document, and it’s impossibly thick with technical jargon. But you can get a hint of the rigor they go into in this analysis by the feds (PDF from DriveElectric.gov), produced in Sept 2024 when the UL 2252 was being written and the feds were providing feedback to UL. It literally gives you over a dozen examples of how these adapters can fail. Thermal overheat sensors in the wrong place. Safety latching mechanisms that don’t latch — or don’t unlatch properly and cause sparks upon disconnect (aka “arcing”). Interfaces that become unsafe after they get rained on for a few hours, or get run over on the asphalt. Check out that PDF and (for example) scroll down to page 19, and see how seriously-smart people are earnestly trying to make these things safe.

Specific details on both of the key two requirements above, as they apply to the two different kinds of adapters, are provided in the two sections below.

As introduced above, the two things you want to look for are a) current carrying capability and b) UL safety certification.

Up to 2020 or so, most EVs on the market pulled 30-32 Amps (6-7 kW) when charging on Level 2, but then with larger batteries (and thus longer driving ranges) the market started to creep up and we now see lots of EVs that pull 48 Amps (10-11 kW). Even if the EV you have now only pulls 30-32 Amps, it’s best to get an adapter that can handle 48 Amps because your next EV might need it.

However, that higher current capability can make the adapter bulkier. The lighter compact units are generally more attractive (e.g. easier to throw into glovebox) but they are less capable and arguably less safe. Make sure to get an adapter that can handle 48 Amps.

The UL standard for charging adapters is UL 2252. Look for a statement from the adapter manufacturer that their adapter has passed testing for this standard, and look for a UL mark directly on the adapter itself. They will absolutely want to crow about this achievement (it’s expensive and difficult for them to get) so if they don’t say it, they don’t have it.

A third consideration is whether the adapter has holes in the latching mechanism that allow you to add a padlock. Since you will typically be using this adapter on a public charging station, and your car will likely release the plug once it’s fully charged, you don’t want someone coming along and stealing your adapter, especially if your EV continues to sit there for hours after fully charged (e.g. overnight at a hotel). Ideally the adapter lets you lock just the vehicle side of the adapter, so that the charging station’s plug can still release (leaving your adapter locked to your car) and then get used by the next EV. Or perhaps you’ll want to lock the other end of the adapter, to lock the adapter to your own home charging station and prevent theft. If the adapter’s padlock hole locks both ends of the adapter, that isn’t great but it’s better than nothing.

Back in the old days, the OG’s of Level 2 adapters were made by TeslaTap and QuickCharge. Both were basically single-man shops (Dave and Tony, respectively) and they took their product quality very seriously. QuickCharge doesn’t appear to offer their old JDapter product anymore, but TeslaTap (now UMC-J1772) is still chugging along, and while they don’t have UL certs I do trust them to make a quality product. Their TeslaTap Mini products (available in both 60 Amp and 80 Amps versions) are rock solid and compact and recommended.

Other recommended adapters are the Lectron and the A2Z models.

As introduced at the top, and similar to the Level 2 adapters, the two main things you want to look for in a DCFC adapter are a) current carrying capability and b) UL safety certification. But the requirements in both cases are quite different here.

Different EVs have different capabilities for how much power (voltage times current) they can pull from a charging station. Most older EV models have lower voltage batteries (like 300-400 Volts) and pull remarkably high currents to still get decent power in. Other newer models have higher voltage batteries (600-800V) and thus pull lower currents for the same power; indeed the main advantage of the higher-voltage drivetrains (e.g. from the Korean models and GM’s newer models) is that with the same current they can deliver far more power into the car during charging, typically twice as much.

Thus an 800V-class EV might draw lower current like 250-350 Amps, but a 400V-class EV might pull 500 Amps. And there’s the rub, because there are DCFC adapters on the market that can only handle the lower currents, like 350 Amps. Notably, some of the OEMs were distributing lower current adapters to their customers, and some of the cheap models you find on Amazon can only handle 350 Amps. It’s best to look for adapters that say they can handle 500 Amps, and it’s OK if they say they can only handle it “temporarily” or for a short surge.

A lower current adapter will overheat when more current is pulled through it than it can handle. Worst case, the adapter melts and damages your car. If the adapter has thermal sensors built-in, it can at least detect the overheating and stop the damage from happening by stopping the session. Therefore you should look for adapters that claim to have thermal overload sensors, but even if they do, they can still function badly due to poor locations inside the adapter. The new UL 2252 standard (discussed in the intro above) specifically evaluates this thermal performance, so again you should be looking for a UL-certified adapter.

A few more considerations, more minor but worth mentioning:

As of 2025, the two leading adapters on the market are:

At this time, I endorse both of those adapters and no others. Both of these handle 500 Amps, with thermal sensors properly designed in, and both have UL 2252 certification (well, as of Jan 2026 the A2Z unit doesn’t yet, but I’m told that’s imminent and the units already sold / for sale are the same as the design that’s about to get UL cert). Note that in both cases, you need the “premium” version of the adapter (Plus and Pro, respectively); the cheaper model does not have the UL cert.

EV veteran Tom Moloughney has been diligently reviewing Level 2 charging stations (for home installs) for many years, initially for his State Of Charge website (now rebranded EVChargingStations.com ) and subsequently via his popular SOC Youtube channel . Lately he has also been evaluating DCFC adapters (for roadtrips), such as this review of the Lectron adapter and this review of the A2Z adapter.

Before heading out on your first roadtrip with one of these adapters, be sure to read through the roadtrip page here, specifically the section that talks about DCFC adapters and how to know if a Tesla supercharger site will work for you. They’re not all the same, and some will not work for you even with an adapter!

The rest of this page provides more background on how we got here.

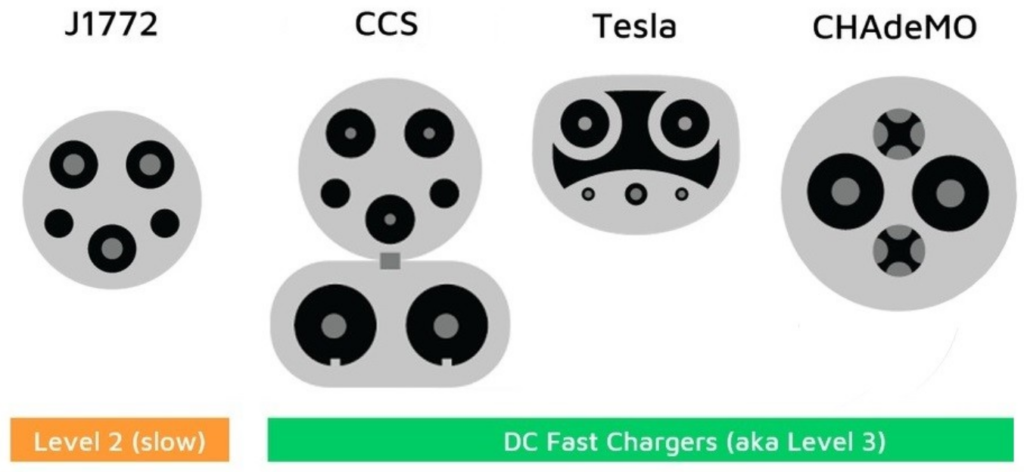

Level 1 and Level 2 are the EV industry’s terms for charging on AC power, via the kind of wall receptacles you find at home; see the home charging page for more about Level 1 and 2. In 2009-2010, the car industry agreed on a Level 2 charging plug standard, called SAE J1772-2009, and all cars sold in North America accept that plug. The industry then started working on the DCFC plug, but more on that in the DCFC section below.

At the time, Tesla was developing their Model S EV, and they were already thinking about a future where Level 2 (AC) and DC Fast Charging could use the exact same port on the car. The non-Tesla industry (via the SAE) had this concept in mind too, of course, but were doing it with a much larger, clunkier interface that Tesla hated. So Tesla came up with their own single proprietary port to handle both, and that launched in 2012 with the market debut of the Model S. Crucially, however, Tesla decided to use the same signaling interface for their Level 2 (AC) charging that was already standardized for J1772 by the SAE (tech detail: PWM duty cycle on control pilot signal with lookup table for resulting amperage). Since the two plugs were using the same signalling language, this meant that it was relatively trivial to then engineer adapters to go between the two physical plug types (J1772 standard and Tesla proprietary), in either direction. Literally the adapter just had to physically fit into the two different plugs on either end, with no signal translation inside required.

Tesla thus shipped these simple adapters with their Model S, at launch in late 2012, allowing Tesla EV owners to use the Level 2 / J1772 stations that were popping up all over the country. Shortly thereafter, Tesla’s own Level 2 stations with their proprietary plug (i.e. Tesla HPWC hardware) started to proliferate at hotels and other destinations via Tesla’s “destination charging” program that offered free stations to site hosts, as long as the site host paid for installation. The market then reacted by creating the opposite adapters — adapters that would allow non-Tesla EV owners (with J1772 ports) to charge at Tesla Level 2 stations (with Tesla’s proprietary plug). Again, because both interfaces use the same signaling defined by the SAE’s J1772-2009 standard, the adapters were simply physical converters to mate between the two different plug shapes.

And so now we pretty much have parity in this segment of the market. Whichever EV you have, you can buy an adapter to charge your car on the “other” type of Level 2 station. See the top of this page for specific guidance on buying a Level 2 charging adapter for charging your non-Tesla EV at a Tesla station.

The story with DC Fast Charging (DCFC) plugs and adapters is more complicated — and contentious.

As described above, by the early 2010s the car industry had agreed on the SAE J1772 signaling standard for slow AC charging, albeit with two different plug shapes but adapters that worked between them.

However, for DC Fast Charging (DCFC), the carmakers did not agree at first and so we started the 2010s fighting out a DCFC standards battle. It was the EV equivalent of the Blu-Ray vs HD-DVD high-def video standards battle, or the VHS-or-Beta videotape battle if you’re that old, except their were three competing standards not just two! Some of the DCFC sites offered “Chademo” plugs (for the Nissan Leaf, mostly), Tesla deployed their “Supercharging” sites (for Tesla models only), and eventually the rest of the auto industry developed the “SAE Combo” plug standard (also known as the Combined Charging System or CCS plug). Literally every other carmaker besides Nissan and Tesla (that means Audi, BMW, Ford, GM, Hyundai, Volkswagen, etc.) used the SAE Combo / CCS plug, and starting in 2015 the CCS plug slowly but surely started taking over the non-Tesla market. However Tesla continued to go their own way with their proprietary plug, which they claimed was also available to other carmakers to use, but Tesla hadn’t done any of the hard standards work (or legal steps) to make it truly available as an option, and thus the rest of the industry ignored them.

While the Tesla Supercharging network is an absolute juggernaut today, in the early days it was still pretty sparse. Nissan had already done a lot of work to deploy their Chademo stations (starting in the early 2010s at Nissan dealerships) to support their affordable Leaf model, so Tesla developed an adapter to allow their new Model S to charge at Chademo stations. This adapter was huge and expensive, and actually took them two years to engineer and finally deliver, but it did expand the reach of the Model S. Years later, Tesla similarly developed a CCS adapter, that allowed Tesla cars to charge at CCS stations. So now Teslas could pretty much charge anywhere, but the reverse was not true — only Teslas could charge at Tesla’s supercharging sites. Tesla’s system was a proprietary system, a walled garden, and even if someone made a physical adapter, a non-Tesla car would never complete the signalling handshake and power would never flow.

This three-way standoff between the three different plug camps persisted for about a decade! First to throw in the towel was Nissan, and by 2020 they had declared that their future US models would switch to CCS. Then, early in 2023 Tesla started doing their first trials of offering CCS plugs at their “supercharging” DCFC sites, with Rivian the first non-Tesla carmaker that was “onboarded” to allow the Rivian models, with their CCS ports, to directly charge at Tesla sites. All of this continued to point to general convergence on the CCS plug as the industry standard. Over the subsequent three years, pretty much all non-Tesla EVs were onboarded into the Tesla system, so a non-Tesla EV owner could charge their CCS car at Tesla sites that support them.

Finally, in May 2023 the big bombshell dropped: Ford was jumping ship from the CCS side over to the Tesla side. Recall that literally the entire auto industry had converged on the CCS standard for DCFC, with Tesla being the lone outlier but also dominating both EV sales and DCFC deployments (their supercharger network). Well, Ford decided they’d seen enough and announced they were jumping over, and within weeks most of the rest of the industry had annnounced the same. Rivian, GM, Volvo, Nissan, Lucid, Mercedes-Benz, the Hyundai group, the VW group, BMW — everyone abandoned CCS. Now, to be clear, they were all just announcing that they would be transitioning over. This transition process would ultimately meant both shipping adapters to their existing customers, which ended up taking 1-3 years depending on the make, and then redesigning their new car models to incorporate Tesla’s port directly on the car.

A critical prerequisite for any of this to happen was that Tesla had finally done the hard work of creating a real standard. Recall that previously Tesla had given only lip service to their proprietary plug being available to other OEMs for use in their car, but none of the other carmakers would touch it because there wasn’t any of the rigorous testing and documentation that a real standard requires, nor any of the software stack to make it a truly multi-vendor interoperable system. Well, in 2022 Tesla had finally started to do that work, and by Nov 2022 had created the North American Charging Standard (NACS). A NACS (“nacks”) plug physically looks exactly like the old Tesla plug, but the signalling protocol it uses inside is actually the CCS communications protocol (ISO 15118), which meant it was leveraging the many years of work that the rest of the industry had already done to create a multi-vendor ecosystem. In early 2023 Tesla started working with the Society of Automotive Engineers (SAE) to create a true standard: J3400. Over the subsequent two years, NACS/J3400 went through the rigorous SAE process — a draft standard, a technical report, and finally a “recommend practice”. All of these are the big-boy documents that the entire industry needed to create both cars and charging hardware that actually works. It was that effort by Tesla that finally got Ford to jump over in May 2023, and which precipitated the entire industry following.

But now Tesla had a new problem: all of their existing Supercharger stations only spoke their old proprietary protocol. For a Supercharger site to support the true NACS standard, and be able to charge non-Tesla cars, every single station would need an upgrade, both hardware (communications protocol boards) and software (CCS transaction processing). Note that this isn’t about the CCS plug — it’s about taking the old Tesla charging system with the proprietary signaling protocol inside it, and converting it to the new NACS standard that supports CCS-like signalling. And so in the first half 2023, Tesla’s engineering team raced to retrofit those NACS updates into as many of their older V3 sites as they could, and then start deploying their new V4 pedestals that supported NACS out of the box.

So, finally, non-Tesla EVs with CCS ports can charge at some Tesla sites, as long as one of two things is true:

For the first case, Tesla had developed their frankly brilliant Magic Dock technology in 2022 and started deploying it in 2023, but then just one year later they sadly stopped activating it at newly built sites. They literally would deploy stations with the Magic Dock adapters built-in, but then not turn them on. This forced CCS EV owners into the second solution: buying their own adapters.

For that second case, the owner has purchased their own adapter, but is relying on the Tesla site having been upgraded to NACS and supporting the CCS signalling. However, you can’t tell just by physically looking at a Tesla site whether it has received that NACS upgrade! You must use the Tesla app, and configure it with your car and whether you have an adapter, and then the map in the Tesla app will only show you their sites that will actually work with what you have. In other words, do not assume that you can use any Tesla site just because you have an adapter! See the roadtrip page here for more on this.

See the top of this page for current advice on which adapters to consider!

Last updated: